Facebook solidarity?

There have been widespread discussions regarding social media as a mobilising instrument, perhaps even that which enabled political action in and through the Arab uprisings. It is also seen to have had the unprecedented effect of “duplicating” such political action across several political contexts. However, the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt, and the “chain reactions” in Libya, Yemen, Bahrain, Syria, as well as the hunger strike campaign in Palestine, all have more important consequences than merely mobilising action.

The work of Palestinian artist and activist Hafez Omar is one of the examples that illustrate the important connections that lie beyond the instrumentalisation of social media in the Arab world. Omar’s work is perhaps most recognised in the recent media campaign supporting the Palestinian prisoners’ hunger strike. However, his work is also very much related to the Arab uprisings, primarily those in Tunisia, Egypt, and Syria.

In an interview with Omar by Jadaliyya magazine, he explains how the Arab uprisings represented a “turning point” in the conception of the role of social media – through which “real time” became the major characteristic of communication, and which as Omar perceives, served “to break the one voice situation” that was dominant in Arab countries.

Although the claim that the “Arab Spring” was a major influence upon accelerating political action in the Arab world, and the Palestinian struggle, might be a reductionist approach towards those struggles, it is unarguable that the role played by social media in the Tunisian and Egyptian uprisings is essential in understanding current political and cultural developments in Palestine.

Omar began his work on the revolutions by creating posters that symbolised and helped mobilise social solidarity amongst the revolutionaries, but also amongst people around the globe, and especially in the Arab world.

The revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt, and the ‘chain reactions’ in Libya, Yemen, Bahrain, Syria, as well as the hunger strike campaign in Palestine, all have more important consequences than merely mobilising action.

As Omar argues, the role of social media in the Arab uprisings shifted from merely perpetuating consumer culture into establishing a space for political action. It is precisely that sort of “feel” that was the most significant effect of the uprisings. In an age thought to be determined by powerful repressive governments, suddenly a new form of old “pan-Arabism” began to occupy the back of our minds. Many Arabs’ solidarity with their neighbours’ demands for social change started to become part of a wider vision, perhaps a fantasy, in which they saw the liberation of their neighbours to be somehow a goal of their own.

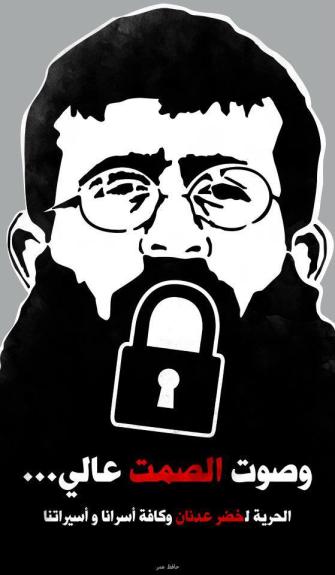

Yet, this form of “pan-Arabism” gained deeper expression through Omar’s most recent and widespread work in support of the hunger strike of the Palestinian prisoners across Israeli prisons. Omar began designing posters in the earlier stages of the hunger strike, which was undertaken by more than 1,300 Palestinian prisoners, yet was perhaps one of the most under-reported large-scale stories in the history of contemporary Western media. He focused on one of the lead figures in the hunger strike, Khader Adnan, who was also on a silence strike in protest against the Israeli oppression that took an administrative form as well. Adnan’s silence was a strong statement that there is no one to speak to in the “Shabas”, the Israeli Prison Service, where Palestinians were imprisoned without charges or sentences, nor were they allowed their rightful legal representation or family visits.

Omar also focused on several other hunger strikers like Thaer Halahleh, Bilal Diab, Hana Shalabi, and Saad Omar – and along with alternative media coverage, the hunger strike campaign was personalised to tell the story of these prisoners, about whom the world knows so little.

In the case of Thaer Halahleh for example, the alternative media began to put into context the reality and lives of these prisoners. They were no longer anonymous terrorists used to make numerical statements as in the case of the Israeli-Hamas prisoner swap. Thaer Halahleh became the father who has never seen his daughter, the man whose administrative detention by the Israeli authorities has lasted for 7 years without charges and under unsubstantiated “secret files” claims.

These images soon became part of everyday street life. In the interview, Omar conveys a wonderful observation: “it’s not about activism; it’s about life. That’s what all the Palestinians do, they’re engaging in the public space and having a political opinion”.

However, along with many people’s attempts to spread the story through alternative and social media, Omar’s famous ‘Shabas’ meme would be one of the most memorable symbols of what was to become global solidarity with the Palestinian hunger strikers. Within a day or two, Facebook was turned brown. Many “wore” the Shabas profile picture, but it wasn’t simply duplicated; it was turned into a meme that was appropriated by the numerous Facebook users according to their various identities.

For Omar, his hunger strike graphic campaign is not a new form of resistance, but continues a long Palestinian tradition that employs political posters. “In Palestine, political posters are a virtue that has existed for years. From the 1960s, the PLO and all other political parties produced hundreds and hundreds of beautiful political posters that helped mobilising and educating people about the cause, and in bringing more solidarity”.

Many Arabs’ solidarity with their neighbours’ demands for social change started to become a part of a wider vision, perhaps a fantasy, in which they saw the liberation of their neighbours to be somehow a goal of their own.

It is thus crucial to understand that contemporary Palestinian resistance, and the Arab uprisings, are not sudden abruptions, but are developments that reach far back, and are ultimately linked to the same history. But more importantly, that pan-Arabism and global solidarity with revolution and resistance, as acts of reclaiming human agency in making social change, can teach us something new. Seeing Omar’s engagement in creating a collectively recognised system of communication as a language of images lifts the concept of ‘solidarity’ to a higher level. Images as political art are not only an instant form of communication, but also one that allows infinite interpretations. The Shabas meme, and its various appropriations, can teach us that in this form of communication lies an implicit awareness, that our inherent pluralisms and differences are also the basic and inherent feature of a communication based on human tolerance.

We must not forget that Palestine does not exist in a separate context, but that a global history binds together all its complications.

By Lama Suleiman